The root of storytelling is pattern

How stories reveal and rehearse what it means to be human

When I think about immigrant families in the US without documentation, I don’t think of criminals. Nor do I have a vague sense of faceless persons, of mannequin-like figures who accumulate as statistics in news stories.

Instead, I see the hard-working Mi’kmaq family from The Berry Pickers, little six-year-old Joe and four-year old Ruthie, who migrated from Nova Scotia to Maine each summer to pick blueberries for American landowners.

I see the title character of Grace, a 14-year-old girl forced to take harsh roads during Ireland’s Great Famine in search of meager sustenance.

I see Laura, Pa, and Ma Ingalls in Little House on the Prairie, traveling by covered wagon towards a better life in Kansas’s Indian country.

Narrative teaches us about the world.

A good story harnesses fundamental patterns of human behavior and reveals those patterns in specific incarnations. The best fiction writers are pattern-seers. Yes, they create something new, but to reflect meaning back to us readers, that newness must be constructed on a foundation of timelessness.

When we encounter a work of fiction we don’t like, it’s often because the characters aren’t believable. What makes us disbelieve a character?

It happens when they have no footing in realistic patterns of behavior. Their desires, motives, fears, and behaviors don’t interact in a coherent way.

To be believable, characters must act according to unspoken rules (what we sometimes call human nature), even as great fiction reveals those rules and therefore teaches us about our fellow human beings.

Fiction is a delicate push-pull between familiarity and discovery.

Fiction is also an acutely recent genre of storytelling, which has been part of the human experience since the beginning. We are driven to understand, and storytelling is our oldest tool for processing facts and events to grasp an understanding.

The clear distinction we recognize between fact and fiction didn’t always exist. Truth was not synonymous with what really happened in ancient times. Hearers of Homer’s Odyssey would not have questioned whether it was factual; that was beside the point. The Odyssey revealed things about the world, like what happens when you violate ethical codes and in doing so, displease the gods. These revelations were, for listeners, the Truth. The same can be said of ancient Icelandic sagas, which narrativize conflict and vengeance among clans. The characters in these legends confronted exaggerated conflicts – menacing giants appeared on Icelandic battlefields – through real patterns of jealousy, deception, anger, rivalry, love, grief, loss.

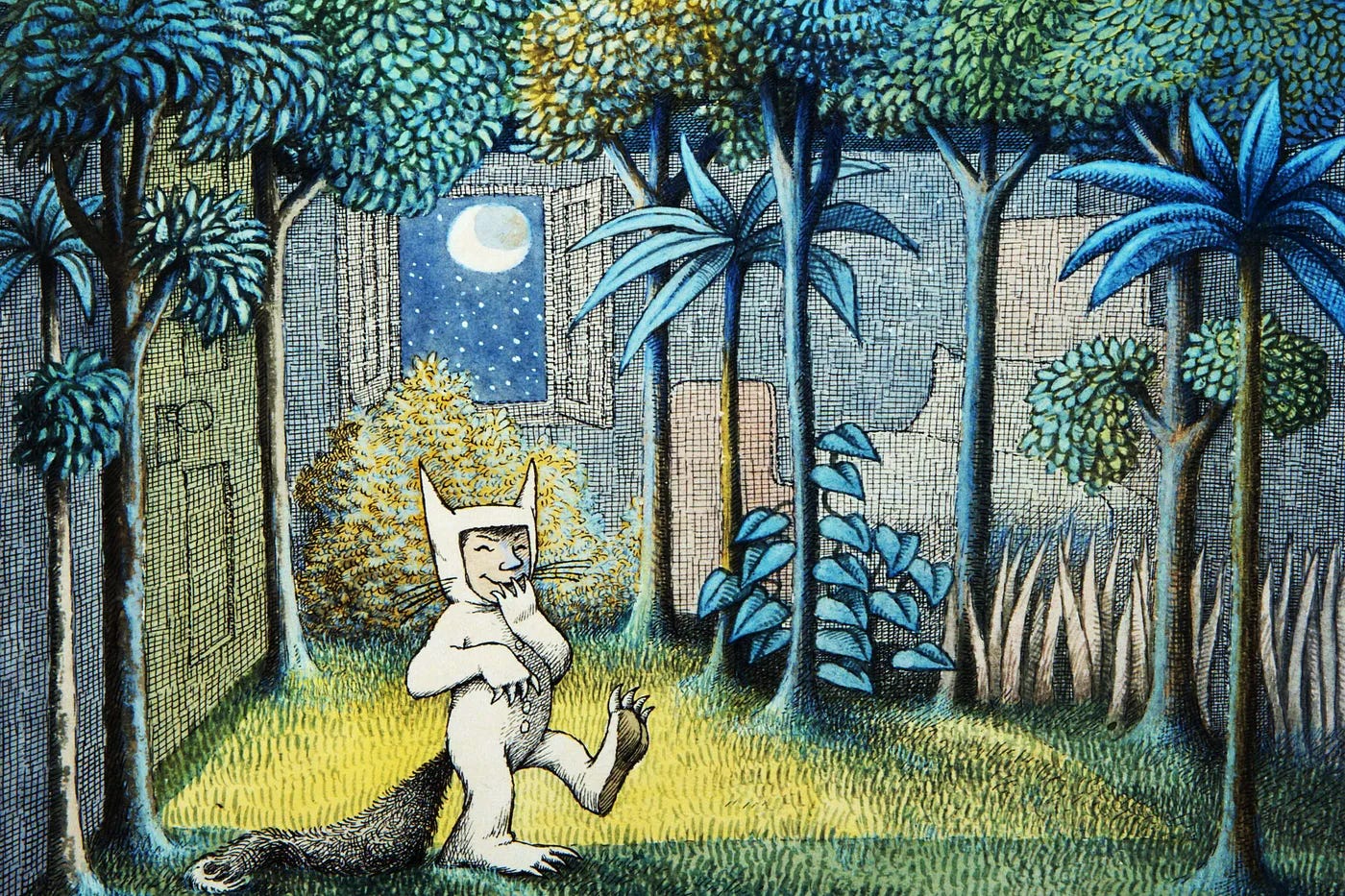

A successful story is a sleight of hand, causing our real-world surroundings to dissolve like Max’s bedroom in Where the Wild Things Are, where the forest grew, and grew, and grew… “until his ceiling hung with vines and the walls became the world all around.” We step into the story, which becomes a kind of simulation of other ways of being.

Through the events of the story and the characters’ reactions to them, we experience an existence outside our own. We don’t just feel for the characters, we feel what it is to be them.

This is only possible if there is an underlying pattern of real humanity on which the author draws.

The science fiction writer N.K. Jemisin understands this. Her novels are set in imagined dystopian worlds, but they are inhabited by humans who behave like we do. To research a novel set amid cataclysmic natural disaster, Jemisin turned to end-of-day-survivalists to probe how people respond to environmental stress. It is the realism of her characters that makes Jemisin’s novels meaningful, despite the unrealism of their surroundings.

Studies have shown that inhabiting literature – getting “lost” in a story – enhances the reader’s empathy. Empathy is a product of literature’s fluency in real patterns of living. When we merge with characters on the page, identifying with their plights, we are primed to spot their real-life doppelgangers and understand something of what they’re going through.

I’ve felt this firsthand. While writing this piece, I scanned through lists of my past reads, pausing on novels and memoirs that particularly illuminated humanity’s mysteries.

A decade ago, I read the anonymous memoir A Woman in Berlin. It narrates the arrival of the Soviet army in war-torn Berlin at the end of WWII. I brought my knowledge of history as baggage to the reading: the people of Berlin, I knew, were complicit in Nazi atrocities, and the Soviet army liberated concentration camps. It is easy to cast the Berliners as the bad side; the Soviets as the good. Yet, the reality is far more complicated. This work shattered the simplistic binary of good and evil through which I had viewed these events, and illuminated patterns of moral compromise, cyclical trauma, and victimhood. My experience with A Woman in Berlin shaped how I see contemporary conflicts, including the Gaza war.

More recently, Small Things Like These reminded me how easily people numb themselves to horrific things happening on their doorsteps. This slim novel is about abuses perpetuated by the Church in a small Irish town and the community that overlooked them. We see our neighbors publicly going about their business and think: Things really can’t be that bad if people are carrying on as normal, so I’ll carry on too. This quietly devastating work reflects a pattern of collective denial and complicity, reminding us that we can blind ourselves to moral crises unfolding in plain sight.

Carson McCullers’s The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, which I read as a teen long ago, caused me to reflect shamefully on how I have avoided and stereotyped marginalized individuals, like the deaf protagonist John Singer. McCullers reveals the pattern of overlooking and underestimating quieter, different voices and the psychic costs of that pattern. The great beauty and tragic events of the story teach us to walk with curiosity and compassion.

I’m certain that the best literature – the best storytelling – illuminates hidden truths about ourselves. I was thinking about this in connection with how institutions use narrative storytelling to predict and plan for humanity’s future.

This is not a modern phenomenon. In ancient and pre-modern times, narrative-driven history was used as a map to the future.

Historians like Sima Qian (c. 145-87 BCE) and Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406 CE) extrapolated patterns from historical events and used those patterns to predict what would happen next. Khaldun, for example, constructed a theory of dynastic rise and fall which, he argued, foretold how current dynasties would fare in the future.

Their methods parallel how fiction has more recently used patterns of human behavior to forecast future societies.

For instance, in the 20th century, writers imagined how emerging forms of society and government would progress. Works such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale carried modern trends forward to their possible outcomes.

The enduring truths these stories revealed are echoed in news headlines:

“We Live in the Reproductive Dystopia of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale,’” blares a New Yorker headline (excavated from the distant past of 2017).

“Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World should be read in tandem to understand today’s trouble times,” is the alarm-ringing title of an essay published in Conversation earlier this year.

If fiction reveals existing patterns of human behavior, it also helps us plan for what lies ahead.

Earlier this year, the UK government hired science fiction writers to brainstorm how things might unfold and what might go wrong. “Taking a very character-based approach can help reveal aspects of future scenarios that you might not necessarily get from a more pulled-out approach,” said novelist Emma Newman at an event organized to prepare for threats ranging from pandemics to cyber and nuclear attacks.

A similar approach comes from the Scenario Game, which was developed by the Bavarian Foresight-Institute, an organization focused on anticipating and preparing for future challenges. The Scenario Game is a toolkit that guides teams to imagine potential future events, for which they then “co-create narratives that are both imaginative and firmly rooted in real-world contexts.”

Understanding potential scenarios is especially urgent today, as we feel ourselves hurtling towards an unknowable future faster than ever before.

When you consider potential futures, what do you envision?

You might have ideas about what could go wrong in the years ahead. I certainly do, shaped by novels like Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (adapted into an excellent HBO series) and films like Children of Men, with its depiction of societal breakdown in the face of infertility, Her, which explores loneliness in a tech-saturated world, and even Wall-E, which offers a satirical but sobering vision of environmental collapse.

Though these works are fictional, they resonate because they rest on realistic human behavior. If (or when) such challenging futures arrive, we may find certain aspects familiar, reminiscent of stories we’ve read or seen on screen. And perhaps, in some small way, we will be better prepared.

Thanks for reading Strange Clarity, where I write about neurodivergence and the hidden patterns of cognition.

If this post sparked something, help others discover it:

→ Leave a comment: even a simple “I was here” makes a huge impact!

→ Share it with someone thoughtful. Substack makes it easy.

More to read:

Personal essay: When you see yourself in your child — and start worrying for two

Commentary: Artificial intelligence isn’t replacing me — it’s extending me

Strange Clarity is reader-powered. If you’d like to support my work, the best way is to subscribe, comment, or share a post that resonated.

With curiosity,

Laura

Reading is so powerful and has saved me a lot of times. I wonder if my empathy comes from books or if I love books because I have a lot of empathy and so can get lost in them more easily... I've written 2 (they were published) and it is really the most complicated endeavour to create convincing, charismatic and motivated humans. I've started and not finished many more novels than I've published, because I just find it so hard. Thanks au-dhd diagnosese shed a bit of light in this too! Working memory issues and extended fiction are maybe not the greatest bedfellows!

I enjoyed this, thanks 🙏